Seeking a Just Environment

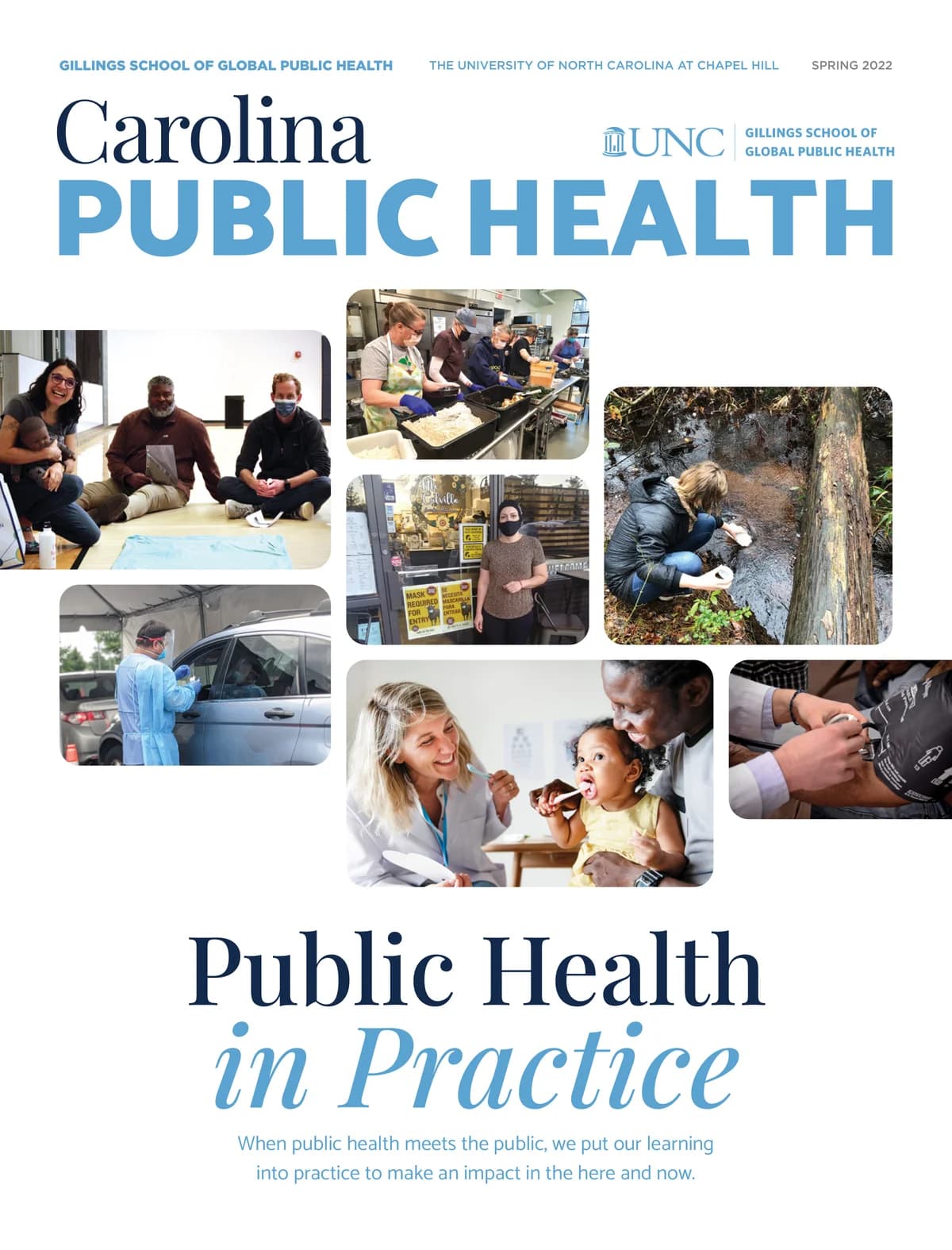

Students in Northcross’ ECUIPP lab work on water testing.

Gillings environmental sciences and engineering researchers are working with communities to create safer and more just environments for those who face environmental health hazards.

Our health is directly impacted by the spaces where we live and work, but there are substantial inequities in access to a clean and safe living environment. Some communities are subject to conditions that contribute to poor health because of institutionalized policies that allow industries to pollute air, water and the very conditions of neighborhoods.

Our health is directly impacted by the spaces where we live and work, but there are substantial inequities in access to a clean and safe living environment. Some communities are subject to conditions that contribute to poor health because of institutionalized policies that allow industries to pollute air, water and the very conditions of neighborhoods.

The most frequent targets of institutionalized policies that contribute to ill health are low-income communities and communities of color, perpetuating structural racism and the health and other inequities that result. Communities can endure environmental hazards for decades, putting them at increased risk for chronic conditions. To overcome inequities, community members and organizations must often take on advocacy work that can play out for years.

Environmental justice (EJ) work at the Gillings School seeks to collaborate with communities through participatory research methods that amplify local expertise and knowledge in the fight against environmental racism. Students, faculty and alumni are applying these methods to work in environmental sciences and engineering, epidemiology, health behavior, and beyond in pursuit of a more just environment.

"It’s a deep honor and privilege to be able to collaborate with communities in this way."

— Courtney Woods, PhD, associate professor

For decades, Associate Professor Courtney Woods, PhD, has been applying her expertise in engineering and toxicology to collaborate with North Carolina communities. Her research team works with local leaders to identify water contaminants and inform supply community policy makers and regulators.

Woods recently collaborated with concerned residents in Sampson County, N.C., to test waterways for pollution from nearby landfills and agricultural operations. By working with the Environmental Justice Community Action Network (EJCAN), Woods’ team identified high levels of polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), emerging contaminants that can suppress immune response and negatively impact cholesterol levels, kidney health and maternal health. PFAS have been called forever chemicals because of their lasting effects. Woods’ team also partnered with the community and Appalachian State University faculty to alert residents to health risks and create strategies to test water supplies.

The success of this endeavor led Woods to co-found the Environmental Justice Action Research Clinic (EJ Clinic) at UNC with funding from Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation. The EJ Clinic partners with EJCAN and the N.C. Environmental Justice Network (NCEJN) to teach students how to apply the principles of participatory research to tackle EJ issues. It is also technical resource for residents seeking policy change.

“Beyond testing for hazardous chemicals and reporting results back to residents,” Woods explained, “we share information on exposure mitigation and well maintenance and information on how to organize residents to connect to public water service, if that is goal. We also encourage residents to get involved locally by attending county council and planning board meetings and public meetings with the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). Collaborating with community organizers in this work is critical because they help sustain the dialogue and momentum and help develop strategy on how research can be used most effectively to support the community’s goals.”

At the Gillings School, Woods co-teaches a class in EJ – formerly taught by the late epidemiology professor Steven Wing, PhD – with the NCEJN and leads Master of Public Health (MPH) concentrations in both Environmental Health Solutions and Health Equity, Social Justice and Human Rights (EQUITY). Through the EJ Clinic, students in these courses and concentrations can build skills to broadly apply work in EJ.

“The Clinic is an opportunity for community groups to gain access to skills and resources that students have, and there are so many topics being addressed,” said Lindsey Savelli, an MPH student in EQUITY who connected with Woods and joined the EJ Clinic to work with residents in Caswell County. “In Anderson, N.C., we’re studying effects of pollution from a proposed asphalt plant and raising awareness of these hazards. We’re also looking at cumulative environmental impacts to see if the DEQ can account for that in permitting processes.”

Woods sees the work as a mutually beneficial way to orient students to community-driven research and practice on real-life public health issues while equipping residents with data and resources to support their advocacy for a healthier community.

“It’s a deep honor and privilege to be able to collaborate with communities in this way,” Woods said.

Graduate research assistant Aleah Walsh collects water samples from a stream in Sampson County.

"Well water, unlike municipal tap water, isn’t tested or regulated. The responsibility falls to private well owners to test."

— Amanda Northcross, PhD, associate professor

At the undergraduate level, Associate Professor Amanda Northcross, PhD, an expert in assessing the health impact of environmental exposures, engages first-year students through a course called Environmentally Engaged Communities and Undergraduate students Investigating for Public health Protection (ECUIPP). This combined seminar and lab introduces participatory research to incoming Carolina students. For many, it is their first encounter with topics related to public health and EJ.

This year, Northcross is teaching two sections of the ECUIPP lab. One section is collaborating with Michael Fisher, PhD, associate professor and faculty at the UNC Water Institute within the Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering, to develop water quality testing kits for well water users in Robeson County. Some students are investigating which kits are cost- effective, while others are investigating the most efficient way for residents to test water.

“Most well water users live in rural areas in N.C., and when we look at the percentage of Black, Latinx and Indigenous people who are relying on well water – those are the groups seeing issues with quality,” Northcross explained. “Well water, unlike municipal tap water, isn’t tested or regulated. The responsibility falls to private well-owners do testing, and many people don't know how or don’t have the resources to do that. We are also working to develop a community advisory board to work with K-12 schools in the area and ensure that folks are learning how to use these kits.”

The second section is working to develop a strategy for low-cost air quality monitoring in Robeson County, where concerns about pollution are impacting cardiovascular risks for Indigenous communities. In alignment with work from Jada Brooks, PhD, at the UNC School of Nursing, and Assistant Professor Radhika Dhingra, PhD, in the Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering, Northcross’ ECUIPP lab team is collecting data from air quality monitors set up at Boys and Girls Club locations around the county and developing a website to communicate findings to the public in an accessible way.

Students in Dr. Northcross’ ECUIPP lab go on a site visit.

Northcross and Brooks have also received funding from UNC’s Whole Community Connection to partner with youth organizations in Robeson County to create maps that identify where the community may encounter hazards and leverage assets to address them. Northcross has also received seed funding from UNC’s C. Felix Harvey Award to address issues of indoor air quality and asthma in Robeson County charter schools.

“All of it is centered around collaborating with community partners so that we can identify where their challenges might be and then work with them to try ensure that we're minimizing the impact of environmental health hazards in a way that’s sustainable,” said Northcross.

Epidemiologists at the Gillings School also have a long history of EJ work, notably, led by the late professor Wing, who for more than 30 years, documented exposure to environmental contaminants and engaged in participatory research to help workers and communities of color in N.C. advocate for a healthier environment.

Though Wing died in 2016, his legacy in EJ lives on through the many alumni he mentored and faculty with whom he collaborated and inspired and through the Epidemiology and Justice Group at Gillings, a student organization that aims to support and educate fellow students on the history and principles of epidemiology for social justice and the practices of community-led public health research. Each year, they help organize the Steve Wing Memorial Lecture, and the School recently developed a fund to help support the annual lecture series.

In commitment to creating a healthier and more just environment, with generous support from alumna Sherry Milan, the Gillings School has newly established the Sherry D. Milan Environmental Justice Scholarship to support students with a demonstrated commitment to work in EJ. As communities across the nation continue to face environmental hazards and the effects of a changing climate, developing skills to apply public health work alongside community experts will be critical to creating lasting and impactful change.

A More Equitable Environment For All

The Gillings community is host to many students, researchers and alumni working towards a more equitable environment for all. Learn more about a few of them:

"I have worked with Lindsay Savelli in the Anderson Community environmental group project in Caswell County. I've also worked with hazard mapping in Sampson County. Additionally, we'll soon be looking at on-site sanitation in eastern N.C. and will be utilizing mixed methods to identify common themes and patterns of on-site sanitation use and barriers to centralized sewer access. We intend on employing community-based participatory research methods and enforcing principles of epistemic justice in this work, particularly as the end results will be policy-oriented."

— Amy Kryston, graduate researcher in the EJ Action Research Clinic

"I feel lucky to have been an advisee of Steve Wing. Through collaborations with Steve and EJN, I was able to help design organizing materials and contribute to Steve’s and Jill Johnston’s work in calculating disparities in exposure to industrial hog operations (IHOs). Those calculations supported civil rights complaints led by community organizers like Naeema Muhammad and Elsie Herring and supported by civil rights lawyers Elizabeth Haddix and Mark Haddix. Since then I’ve contributed to scientific public comments (2019, 2020) and legal challenges (2021, 2022) to environmental justice issues in N.C. and abroad. I also lead a Duke Data+ data science team in building a pilot Environmental Public Health Tracking tool for the N.C. Division of Public Health, enabling them to apply for CDC funding to sustainably support and release that tool publicly. I’ve continued to support that research where I can, including as part of Arbor Quist’s dissertation committee."

— Mike Dolan Fliss, PhD, MPS, research scientist at the UNC Injury Prevention Research Center and 2019 doctoral alumnus in epidemiology

"My dissertation title is Investigating Relationships Among Environment Exposures, Demographic Characteristics, and Preterm Birth. In this dissertation, I examine how sociodemographic characteristics (such as race and maternal education) modify the preterm birth risk. We are using a N.C. Birth Cohort database from 2000-2013 to understand how climate change can affect preterm births. I utilize exposure databases (air pollution, metal mixtures in drinking water, and heat) to understand the differential exposure to vulnerable communities, specifically communities of color. We are also doing a similar project using Lineberger Cancer data and the well water database to associate metals in drinking water to cancer incidence, then examine how sociodemographic characteristics modify cancer risk."

— Eric Brown, doctoral student in environmental sciences and engineering