All past articles

Browse through our archives of Carolina Public Health articles from UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health. Have a specific topic in mind? Use the search and filter functions below. Note: We are in the process of transferring all past issues into this platform, so more articles will be added soon!

But our field is no stranger to these challenges. The strong legacy of our work in public health endures, both at the Gillings School and broadly. Times of trial reaffirm our commitment to the well-being of the people we serve — the state of North Carolina and communities across the world — and they underscore how necessary our mission continues to be.

What gives me hope is you, our extraordinary community who supports public health because we believe a healthier, more just world is possible.

What sets the Gillings School apart as a top school of public health is not just our expertise but the drive and creativity that our students, faculty, staff and alumni bring every day. Our reputation stems from teaching and learning, research and practice, support operations, and community engagement — all working together to make an enormous positive effect.

As you read this report, you’ll see our collective impact in every program and partnership, not only in the immediate outcomes but in the long-term changes that unfold over years. Public health often works quietly and persistently, with research and community action laying the groundwork for policies, behaviors and systems that evolve gradually to improve lives.

Standing on a resilient legacy, we will continue to build the future of public health together.

Dr. Nancy Messonnier, Dean and Bryson Distinguished Professor in Public Health, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health

———

Our Priorities

This year, we focus on three critical priorities that reflect urgent needs and extraordinary opportunities.

1. State of North Carolina

We’re promoting healthier lifestyles and informed health choices while improving prenatal care and reducing maternal and infant mortality, all with the goal of increasing the state’s health ranking, which currently sits at 30th in the nation. Our comprehensive approach to the opioid crisis has contributed to a remarkable 27% reduction in overdose deaths in the state between 2023 and 2024 — demonstrating what’s possible when research meets community action.

2. Generative AI

We’re empowering outstanding interdisciplinary AI research that optimizes public health efforts, such as cancer screenings, infectious disease tracking and the development of large language models that support patient treatment adherence. Our portable AI ultrasound devices assist pregnancy care providers in low-resource settings, demonstrating how innovation bridges gaps in access and equity.

3. Clean air and water

We’re conducting cutting-edge studies on pollution sources and health impacts, collaborating with communities to respond to disasters like Hurricane Helene and improve well water quality, and developing innovative methods to address harmful chemicals like PFAS in both air and water. Protecting these vital resources safeguards health and ensures a sustainable future.

Dana Rice, DrPH

Associate Dean for Academic Affairs

Our 64 academic programs provide students with up-to-the-minute public health content and skills development in broad public health areas, and our curricula provide our graduates with the workforce-ready preparation needed by employers.

This Fall, we welcomed the inaugural class of 34 students pursuing the new Bachelor of Science in Public Health degree in Community and Global Public Health, which prepares students to work in partnership with local and global communities to identify, assess and address health programs and to achieve health equity.

The Master of Public Health (MPH) program was pleased to welcome MPH@UNC online students to campus for two immersive experiences. The Fall immersion aligned with Practicum Day, the Experience Gillings Open House and the National Health Equity Research Webcast. The Spring immersion coincided with the Minority Health Conference. The MPH program reinstated the in-person Practicum Day event, which showcases and celebrates the previous academic year’s practica and their impacts. (See facing page for practicum impacts.)

Doctoral programs continue to prepare students as highly skilled, highly employable researchers and leaders. More than 95% of doctoral graduates were either employed, engaged in a post-doctoral fellowship or pursuing other educational opportunities 12 months after graduating.

Laura Linnan, ScD, stepped down from her role as senior associate dean for academic and student affairs after 10 years of invaluable leadership. Dana Rice, DrPH, began as associate dean for academic affairs after having first served for four years as the school’s inaugural assistant dean for master’s programs. We also welcomed Ciara Zachary, PhD, as assistant dean for master’s programs, and Shelley Golden, PhD, as inaugural assistant dean for doctoral programs.

The student affairs team has strengthened the career services unit, led by Greg Bocchino, EdD. His team is rolling out a robust career services plan, responsive to student feedback and integrating ideas from different degree program leaders, to help graduating students — and early career alumni — adapt to a rapidly changing work environment. Between 97-99% of students find employment or pursue further education within 6-12 months of graduating.

Mark Holmes, PhD

Senior Associate Dean for Faculty and Staff Affairs

The Gillings School also has a new Faculty and Staff Affairs unit that will help ensure all employees get the tailored resources they need to grow in their careers, including support for career planning for any staff member who is interested. A key dimension of the new unit will be its focus on supporting faculty — and collaborating with career services — to strengthen student mentoring and career readiness. The Faculty and Staff Affairs unit will also guide implementation of the newly adopted Gillings Community Plan. The team is currently rolling out opportunities for faculty, students and staff to come together to dialogue across differences through its Heels for Healing program.

This year, the team relocated to a new suite to offer more enhanced services in response to student survey results. The new activities and programs support career planning and decision-making, resume/curriculum vitae (CV) and cover letter reviews, interview preparation, salary negotiation, networking, and job search resources. They also urge students to take an early and active role in their own career development by prioritizing continuous learning, attending events and workshops, and seeking out meaningful opportunities to build their professional networks. The team also provides support for alumni, many of whom have experienced upheaval recently in the public health job sector.

Several members of the team have recently won awards for their good work ...

Lidia Colato Raez

Assistant Director for Career Services and Employer Engagement

Colato Raez was recently honored with the Employee Forum’s Professional Excellence Award. She was nominated by her peers for going above and beyond her assigned duties and exemplifying outstanding dedication and collaboration. In the past year, Colato Raez coordinated career information sessions on short notice, led efforts on expanded web resources for career services and maintained a strong relationship with the University Career Center’s Employer Relations team.

Derek Just

Assistant Director for Student and Alumni Career Services

Just has become the resident expert on generative AI in career services. He recently built an AI-enabled cover letter generator called CoverCraft to help Gillings students and alumni. The user enters their resume and the description of the job they are applying to, and the tool helps create a compelling cover letter. The website features a chat section to refine and improve the letter.

Greg Bocchino

Senior Executive Director for Career Services and Professional Development

Bocchino is a longtime-Gillings School leader in student support, leading programs to help students and alumni develop skills. He is also now serving as the new chair-elect to the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH) Career Services Assembly in a three-year position. Bocchino will be helping to lead the collaborative career services efforts for students, faculty and staff across nationwide schools and programs of public health.

———

Visit the Gillings School Career Services website to learn more, book an appointment or stop by their newly redesigned Career and Student Lounge in Rosenau 263.

Full story: https://sph.unc.edu/sph-news/award-winning-career-services-team-helps-gillings-students-focus-on-the-future

Alexia Kelley, PhD

Interim Associate Dean for Research

As we navigate the changing landscape of federal funding and policies, we are strategically developing a diverse research portfolio through innovative partnerships across academia, industry, government and community organizations. Looking ahead, we are focused on positioning ourselves at the forefront of public health research by leading with innovation and collaboration.

Check out some of the ways Gillings School researchers are addressing North Carolina’s health challenges while maintaining a strong global presence.

WIC as a maternal safety net

Maternal and child health researchers partner with USDA/WIC to implement evidence-based interventions that help staff and families recognize early warning signs of maternal morbidity. This approach can extend to health departments and Federally Qualified Health Centers, making it a scalable safety net for moms.

Researchers: Larelle Bookhart, PhD, Dorothy Cilenti, DrPH, Christine Tucker, PhD

Getting lead out, globally

Environmental sciences and engineering research on lead in drinking water drove World Health Organization guidance and a global pledge to eliminate lead pipes by 2040. Major implementers like World Vision and the World Bank have already shifted procurement, protecting millions of families from toxic exposure.

Researchers: Michael Fisher, PhD, The Water Institute

Drone-delivered defibrillators

Epidemiology research proved that autonomous drones can deliver AEDs to cardiac-arrest scenes, cutting critical minutes before emergency medical service arrives. This innovation could save countless lives by bringing lifesaving tech to neighborhoods fast.

Researcher: Wayne Rosamond, PhD

Safer jobs, healthier workers

Total Worker Health® research in health behavior improves safety and well-being for employees nationwide, influencing the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s policy and training the next generation of workplace health leaders. These interventions reduce chronic disease risk and injuries where people spend most of their day — on the job.

Researcher: Laura Linnan, ScD

Diagnosing cancer sooner

Epidemiology and health policy and management researchers led the first U.S. study on emergency cancer diagnoses, revealing that up to 40% of cases start in the emergency room. Their work drives system changes to catch cancer earlier.

Researcher: Caroline Thompson, PhD

Food as health

Through a partnership with Equiti Foods, nutrition researchers help bring 1,200 healthy meals per week to Medicaid recipients in the N.C. Healthy Opportunities Pilots. The program also creates jobs and farm demand in rural communities, linking nutrition security with local economic growth.

Researchers: Alice Ammerman, DrPH, Lindsey Haynes-Maslow, PhD

AI for safer pregnancies worldwide

Biostatistics researchers codeveloped an AI tool for gestational age estimation using blind ultrasound sweeps, validated in underresourced settings across Africa and India. This innovation enables accurate pregnancy dating without expensive equipment or highly trained personnel. It is now being considered for global scaleup to improve maternal and newborn outcomes.

Researchers: Michael Kosorok, PhD, Jeff Stringer, MD

Healthy veteran communities across N.C.

Researchers in public health leadership and practice lead a $6.8M initiative to improve veteran health through community-based partnerships, resource mapping and best-practice toolkits. The project has engaged 30+ students and expanded to multiple N.C. counties, creating a replicable model for rural veteran well-being.

Researchers: Vaughn Upshaw, DrPH, EdD, Aimee McHale, JD

Nabarun “Nab” Dasgupta, PhD, holds many titles at UNC-Chapel Hill: Innovation Fellow at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, senior scientist at the UNC Injury Prevention Research Center and leader of the UNC Street Drug Analysis Lab.

Now he can add “genius” to that list.

Dasgupta has been awarded a 2025 MacArthur Fellowship, known as the “genius grant.” The honor, announced Oct. 8 by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, recognizes Dasgupta’s work as an epidemiologist and harm reduction advocate who combines scientific studies with community engagement to reduce deaths and other harms from drug use and overdose. Dasgupta and his team have played an important role in the national response to the opioid epidemic.

“Our mission is science in service. We want people to have access to the best knowledge and tools, so they can make better decisions about what they put in their bodies.”

— Nabarun “Nab” Dasgupta

“Our mission is science in service,” Dasgupta said. “We want people to have access to the best knowledge and tools, so they can make better decisions about what they put in their bodies. This award is a testament to hundreds of community programs and health departments we serve, where lifesaving work happens.”

Dasgupta’s Street Drug Analysis Lab tests community-donated samples from around the country to determine what is in street drugs, then makes the results public in an online database. To date, the lab has completed more than 16,000 analyses with atomic precision. Understanding the makeup of these drugs helps individuals make decisions about their drug use and allows community members and first responders to prepare and provide proper care.

Integrating molecular data and community-based problem solving, Dasgupta uses his Carolina training as an epidemiologist to isolate trends and illuminate the bigger picture. His passion is telling true stories about health with numbers. Those interested can follow the lab’s work in their newsletter.

“Our amazing teams pack boxes, analyze drug samples and process large volumes of data every day, in the hope that our neighbors have autonomy to lead healthier lives,” he said.

“Doing this work at Carolina is thrilling. Whenever we detect a street drug that’s never been seen before, we can call up world-class experts on campus and get immediate insight. The science that used to take years, we now do in weeks because we are focused on the socially relevant and actionable.”

In addition to analyzing street drugs, Dasgupta has worked for nearly two decades on broadening access to naloxone, which reverses opioid overdoses. He collaborates with people who have experience with drug use or its consequences to design effective, evidence-based interventions that respond to the needs of those who use drugs and community-based organizations that support them.

“We are immensely proud of Nabarun Dasgupta for receiving a MacArthur Fellowship,” said Chancellor Lee H. Roberts, JD. “His groundbreaking work exemplifies Carolina’s mission to advance knowledge in service to society. This award honors his dedication and impact, as well as the collaborative spirit and commitment to the public good that define our faculty. Nabarun’s leadership and scholarship are making a tangible difference in North Carolina and beyond, and we celebrate this well-deserved achievement.”

“Nabarun Dasgupta’s recognition as a MacArthur Fellow is a powerful affirmation of the lasting impact his research has had on the communities he serves,” said Penny Gordon-Larsen, PhD, vice chancellor for research. “Addressing opioid overdose deaths, one of the most urgent public health challenges of our time, demands not only scientific excellence but also compassion, vision and collaboration. His work exemplifies how research can both advance knowledge and directly improve lives, exactly what we strive for every day at UNC-Chapel Hill.”

“Nabarun Dasgupta is such a fitting recipient of this prestigious recognition as the first Gillings Innovation Fellow as well as Senior Scientist at the UNC Injury Prevention Research Center,” said Nancy Messonnier, MD, dean of the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health. “He specializes in turning research into practice, and through his work, he amplifies community and patient voices in public health and provides innovative health-tech and community-based solutions. He co-founded a non-profit in Wilkes County, N.C., which was the first of its kind to provide the antidote that reverses overdose to pain patients and people who use drugs. His originality, insight and potential are just a few of the values he shares with the MacArthur Fellowship, and we are immensely proud of his dedication, selflessness and accomplishments.”

Full story: unc.edu/posts/2025/10/08/nabarun-dasgupta-wins-macarthur-genius-grant

While no amount of alcohol is considered safe for health, excessive drinking increases the risk of alcohol poisoning, violence and injury, car accidents, and long-term health problems like heart and liver disease and cancer. In 2023, more than a quarter of Americans between ages 18-25 reported binge drinking — consuming 4-5 drinks on one occasion — in the past month, and more than 2 million reported high-intensity drinking — a risky behavior indicating consumption of more than double the binge drinking threshold.

“Our research has shown that high-intensity drinking is a relatively frequent behavior that has severe consequences,” said Melissa Cox, PhD, assistant professor of health behavior at the Gillings School, who is leading the development of the mobile health solution. “There are various environmental determinants — like where you are and who you’re with — that might facilitate this type of behavior, and these are the kind of factors our mobile app is trying to mitigate.”

The app uses an algorithm that leverages data on a user’s location and social situations to trigger real-time text messages.

The mobile app uses an algorithm that leverages data on a user’s location and social situations to trigger real-time text messages, prompting the user to consider how many drinks they’ve had and how to reduce their risk for negative consequences because of drinking. Users will complete daily reporting on the amount of alcohol they’ve consumed the previous day and the potential health effects it may have provoked. During the initial pilot period, the app will also survey users 30 days after the trial to track any changes in drinking behavior and related harms. This type of just-in-time-adaptive-intervention (JITAI) approach was informed by work completed by the Gillings Innovation Lab-funded smart app for weight management led by Gillings School researchers Deborah Tate, PhD, Carmina Valle, PhD, and Brooke Nezami, PhD.

“It’s a creative way of integrating technical information gathering with what we know from the evidence base works to address high-risk drinking and putting it all together to generate this intervention,” Cox explained.

The study team is working with UNC’s Connected Health for Applications and Interventions (CHAI) Core to help shape the app, deploy the algorithm and ensure it protects privacy. Cox says the app will have high levels of encryption, and all data collected from users will be voluntary.

Startup funding from the National Institutes of Health and Innovate Carolina’s Translating Innovative Ideas for the Public Good (TIIP) Award is providing critical support for the app, which is still in its early pilot phase of trial to determine whether it can be a feasible solution to address high-risk drinking. These grants are a boon to researchers who want to innovate new solutions to potential public health challenges but face a mountain of startup costs that other grants will not cover without proof of concept.

“We wouldn’t have been able to do what we’ve done thus far without the Innovate Carolina funding,” Cox said. “We’re not even building the full app yet; that’s the expensive part. Right now, we’re developing something that has a look and feel of an app, because tech-based behavioral interventions are expensive. It takes a lot up front to even get to the point where you can rationalize the larger investment in building native apps.”

Cox and her research team began the pilot phase of testing in early fall of 2025 and hope to recruit users between 18-25 who come from a broad section of the general public, not just college students. The data from the pilot will help them determine the feasibility of building a more robust app that can ultimately prevent harms from high-risk alcohol use by intervening in drinking choices in real time.

Pivoting to Meet the Moment

We recognize the profound impact that shifting administrative priorities has had on our Gillings School alumni who work in global health. In response, we have deepened our commitment to supporting these professionals through strategic collaboration with Gillings Career Services. This partnership has enabled us to offer tailored career pivot resources with the goal of ensuring every alum feels seen, supported and equipped to navigate their next chapter with confidence.

Gillings stands beside its graduates not only during times of achievement but also in moments of challenge.

The impact of this support has been both tangible and transformative. Many alumni have successfully transitioned into new roles that align with their values and expertise, often discovering renewed purpose in areas they hadn’t previously considered. Beyond job placement, our efforts have fostered a sense of community and resilience, reinforcing the message that Gillings stands beside its graduates not only during times of achievement but also in moments of challenge. This initiative reflects our enduring commitment to public health leadership and the people who carry it forward, during good times and challenging times.

Global Hubs

Designed to establish a sustained presence in select geographic regions, the Global Hubs aim to provide high-quality, immersive learning experiences for students while enabling faculty to advance strategic public health initiatives collaboratively with in-country partners. Opportunities in Malawi, Vietnam and Zambia are made possible through a vital partnership with the UNC Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases (IGHID).

In summer 2025, 7 students worked with UNC Project Malawi (3), UNC Project Vietnam (3) and UNC Global Projects Zambia (1). Since the start of the Global Hubs in 2019, the international global hubs sites have helped train 28 Gillings Master of Public Health (MPH) students.

Student Spotlight

One example of student work includes Charlotte Russo, who collaborated with oncology staff, clinicians and pathologists in Malawi to design a qualitative study protocol that will guide future research on barriers to timely cancer diagnosis. This research will lay the foundation for interventions aimed at strengthening diagnostic pathways and advancing equity in access to cancer care.

Faculty Spotlight

Professors Vivian Go, PhD, and William C. Miller, PhD, both Gillings faculty and members of IGHID, have partnered closely with Vietnam’s Ministry of Health and Hanoi Medical University (HMU) to conduct research that has directly shaped national HIV policy and public health education and recently received honorable professorships from HMU for their outstanding contributions in training, scientific research and development of international partnerships for over a decade.

Global Research Impact

We have more than 80 faculty members who have currently or previously been engaged in global research. Many of these faculty have cultivated long-standing partnerships with international collaborators and organizations. One example is the work of Nora Rosenberg, PhD, whose team developed and tested a couples-based HIV program that encourages joint counseling sessions for pregnant women living with HIV and their male partners to foster mutual support and better adherence to HIV treatment. The findings are relevant to 1.2 million women living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa who become pregnant each year and their male partners.

Innovation Strategy Advisor: A newly established faculty overlay role, held by Will Vizuete, PhD, expands Innovation@Gillings’ reach to drive public health impact.

Faculty Innovator Group: A community of innovation-focused faculty fostering collaboration, idea sharing and networking to address global health challenges. The group hosted a fireside chat with faculty innovators and awarded four micro grants to fund prototyping activities beyond traditional federal support.

Gillings Student Pitch Competition featured 12 teams and 10 coaches:

- First Place ($3,000): Sensible — A diagnostic menstrual pad screening for cervical cancer, coached by Erik Eaker.

- Second Place ($1,500) & People’s Choice ($400): Olea Health — AI-driven, SMS-based health education for underserved populations, coached by Sammy Orelien.

- Third Place: MedFam ($750) — Discounted lodging for families in medical emergencies, coached by Richard Kelly.

Startup: Couplet Care Inc., which markets bassinets that safely connect parents and newborns, completed its first commercial sales in N.C. and M.I. The patented technology was developed over nine years by a team led by UNC and Gillings-affiliated researchers Kristin Tully, PhD, Catherine Sullivan, MPH, Carl Seashore, MD, and Alison Stuebe, MD.

Intellectual property: AI-driven ultrasound technology by Jeff Stringer, MD, Ben Pokaprakarn, PhD, and Michael Kosorok, PhD, was patented and licensed to expand fetal imaging access in rural and low-resource settings.

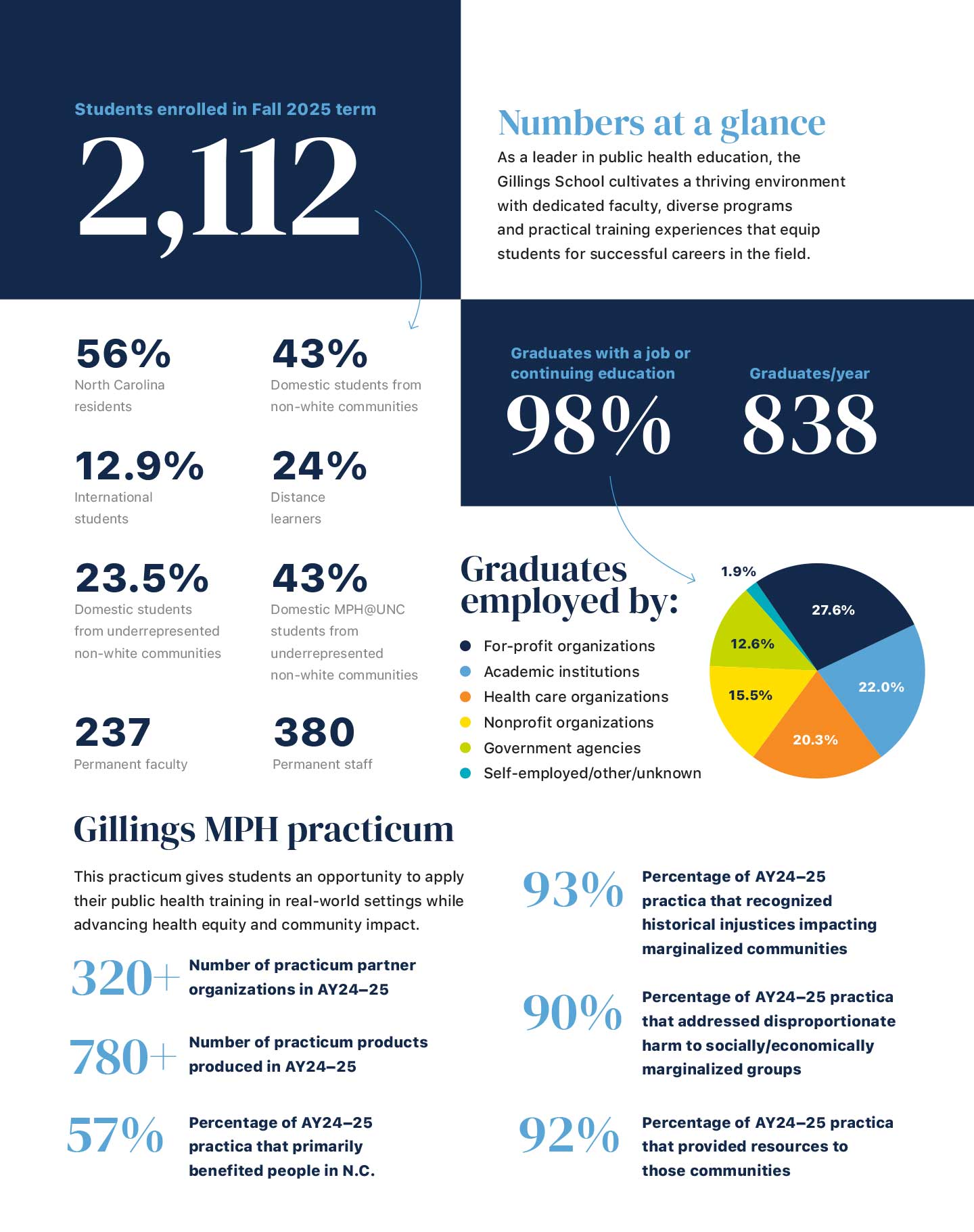

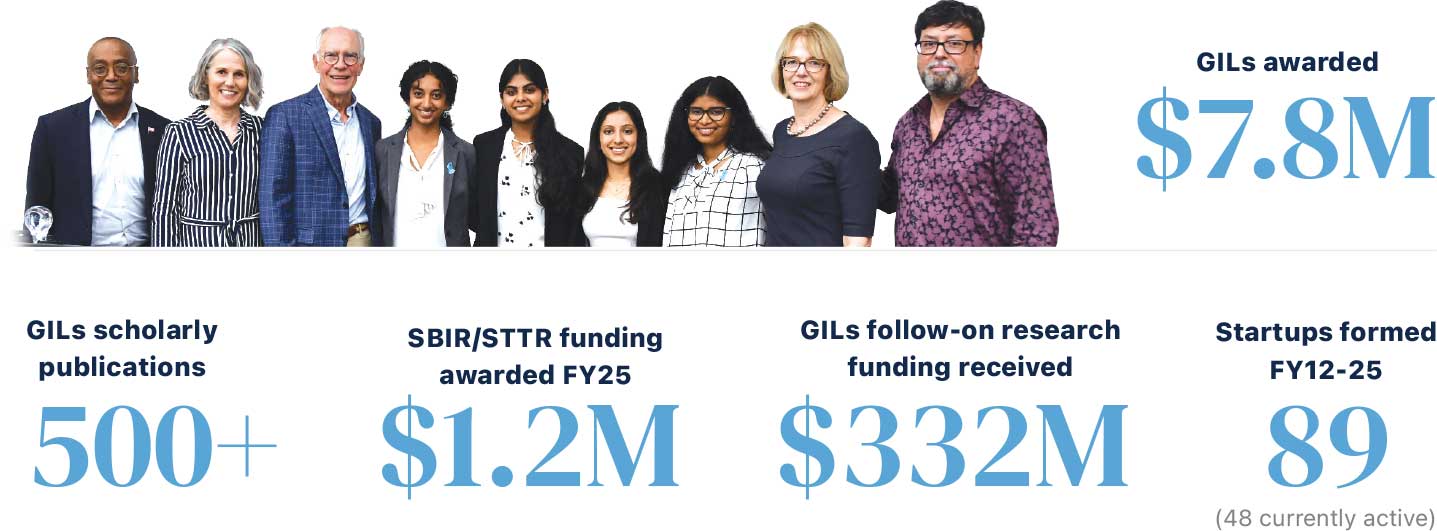

Pilot funding: $7.8M invested in 44 Gillings Innovation Labs has generated $332M in follow-on funding, 500+ publications, three startups and two patents. Six active labs on generative AI reached midpoint with $6M follow-on funding and new invention disclosures.

- The U.S. has one of the highest rates of preterm births among high-income countries, but experts across the Gillings School in maternal and child health, epidemiology, health behavior, and environmental sciences and engineering are working to improve them. This includes research on lowering the risks of chronic disease, improving maternal health care access and ensuring water is free of chemicals that can increase birth risks.

- The water in your faucet was probably clean this morning when you brushed your teeth, but disasters like Hurricane Helene have shown us how quickly water quality can be impacted, even in our own backyard. Public health work at the Gillings School is innovating new ways to ensure we have safe and sanitary water.

- Since they were introduced in 1968, seatbelts have saved more than 300,000 lives, according to data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and they’re just one example of the important public health interventions that keep us safe. Gillings School faculty in health behavior and the Injury Prevention Research Center are also collaborating with state and national agencies to promote traffic safety policies and design safer roads.

- Gillings School health behavior researchers have long been at the forefront of tobacco control. Their work helped inform the implementation of warning labels, smoke-free policies and youth prevention programs. Thanks to these efforts, rates of smoking in the U.S. have plummeted 73% among adults and 86% among youth, according to the American Lung Association.

- Vaccines remain one of public health’s most powerful tools, and Gillings School researchers in epidemiology and health behavior are leading efforts to improve vaccine access and trust. Thanks to vaccines and public health policies, deadly diseases like smallpox, measles, hepatitis, malaria, polio and so many more can now be a worry of the past — but only if we continue to support and promote vaccination and vaccine development.

- Crosswalk imagery is one of the many ways public health has helped to keep pedestrians safe. Faculty at the Gillings School affiliated with the Highway Safety Research Center have tested variations of universal pedestrian signs that were not language dependent, leading to wide adoption across the globe.

No results found

There are no results with your selected criteria.

Try changing your search.